Article: The Emergence of Minimalism

15 Jan 2020

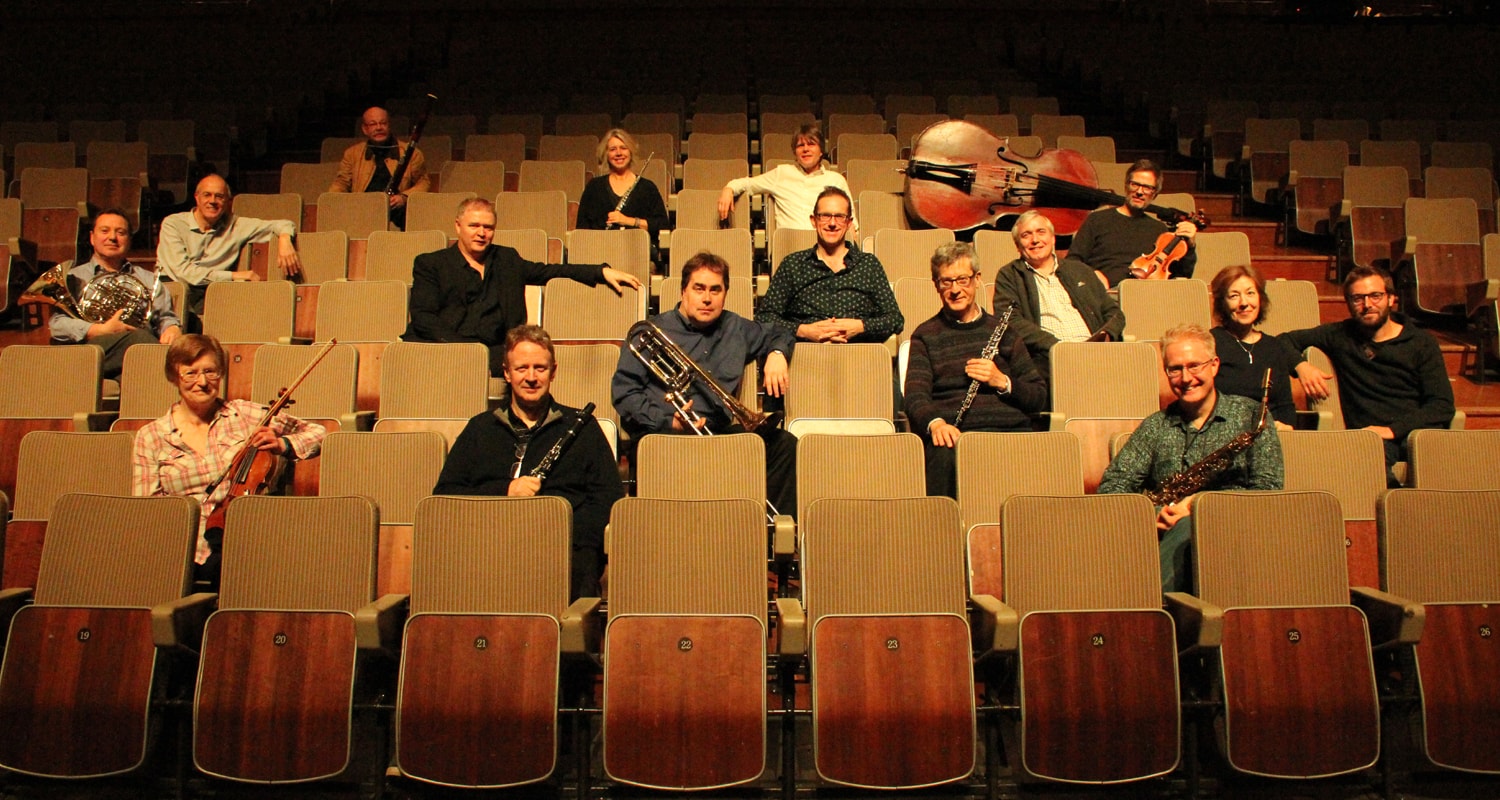

Image: London Sinfonietta in Queen Elizabeth Hall, circa 1970

When the group was founded, it was picking up pieces that fell between the cracks in normal concert routines, not fitted to regular orchestras or chamber teams. Now we have a whole culture of the contemporary ensemble, a formation that most composers today find more natural than the standard symphony orchestra, and one that has spread to the major cities of the world – Paris (Ensemble intercontemporain), Frankfurt (Ensemble Modern), Vienna (Klangforum), New York (ICE, Talea), Cologne (musikFabrik), Birmingham (BCMG) – all as a result of what happened here in London in 1968.

The initiative taken then by David Atherton as conductor and Nicholas Snowman as administrator was not entirely without precedent. Pierre Boulez’s Domaine Musical, founded in Paris a decade and a half before, provided a model, but one to be adapted to current conditions of state funding, open programming and – bang next door to what was then the capital’s single major concert hall – a new, appropriately sized venue. Southbank Centre’s Queen Elizabeth Hall had opened just 10 months before the London Sinfonietta’s first concert, and it became the outfit’s regular home, allowing an audience of close to a thousand people to peer down into the workings of new music as it came into being.

Before the Queen Elizabeth Hall closed for refurbishment in 2015, only about a quarter of the group’s several thousand concerts had taken place there. The London Sinfonietta has played elsewhere in London, from the Asylum Chapel in Peckham to the Royal Opera House, and elsewhere in Britain, from St Magnus Cathedral in Orkney to Stansted Airport, and all over the world. Restlessness is an inbuilt characteristic.

Restlessness is an inbuilt characteristic

Being in the right place at the right time has also played a part. Starting from nowhere in planning a first concert, for 24 January 1968, Snowman remembered an old school friend. John Tavener’s The Whale needed a first performance, a tour of cetacean lore studded with everything from late Stravinsky (at a time when the composer was still alive and writing) to pop culture. In the heady atmosphere of those distant days, when even the moon was coming within human reach, the piece struck a chord. It led to a BBC TV feature and a recording on The Beatles’ Apple label – the London Sinfonietta’s debut disc.

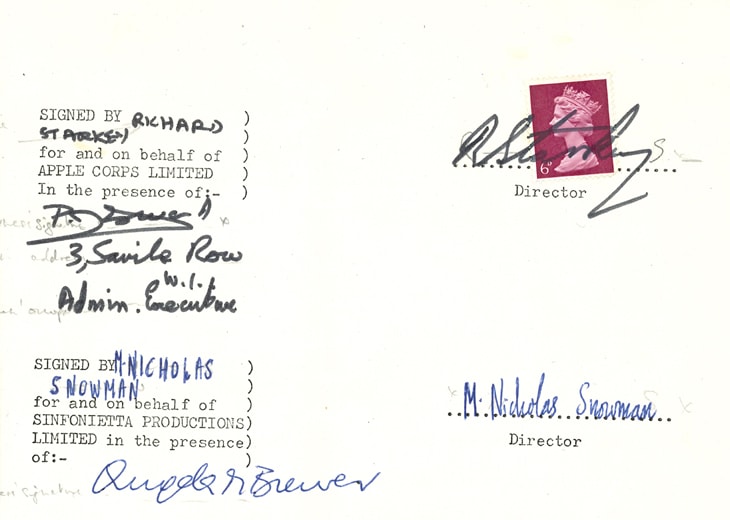

Image: signed recording contract for The Whale with Ringo Starr and Nicholas Snowman

Over the next two years, the period of its infancy, the London Sinfonietta discovered other British composers with whom it would have longer associations – among them Harrison Birtwistle, who gave the group its first classic, Verses for Ensembles. With its trumpet soloists mounting podia, its woodwind and percussion players switching positions, and its crisscrossing conditions of eruption and stillness, the piece startlingly redefined orchestral music as theatre. It also initiated a synergy between composer and musicians that was to result in Silbury Air, Secret Theatre, Ritual Fragment and so many more.

When it was first played in February 1969, Verses for Ensembles was followed on the programme by Dvořák’s Serenade in D minor, but soon the London Sinfonietta steered away from including older pieces, recognising what riches it had in new music and 20th-century classics. By the end of 1970 the ensemble had played music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Hans Werner Henze and Iannis Xenakis on the one hand and Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg and Edgard Varèse on the other. It had touched the intermediate generation of Roberto Gerhard, Witold Lutosławski and Michael Tippett, and its commissions had opened new musical vistas: the ritual interchanges of Verses for Ensembles, the electronic modulations of Roger Smalley’s Pulses 5×4, the encounter with jazz in Don Banks’ Meeting Place. It had become, thoroughly, a new-music ensemble, and had set the pattern for its successors.

Then came the astonishing month of June 1971, when the London Sinfonietta played four concerts in the ISCM Festival, welcomed Luciano Berio and Pierre Boulez as guest conductors, and completed a tour with dates in Austria, Italy and the Netherlands. Further landmarks followed: a first Prom two months later, and the next year a collaboration with David Munrow’s Early Music Consort, the two groups playing together in a piece by Elisabeth Lutyens, the first woman commissioned by the London Sinfonietta. By 1973 there were more than 40 concerts on the group’s agenda. So it continued: the London Sinfonietta had its main-stage season, its national tours sponsored by the Arts Council, its BBC broadcasts, its European dates and its recording sessions (for essential albums devoted to György Ligeti, Hans Werner Henze and Harrison Birtwistle, amongst others). It also gained a major new ally in Simon Rattle, who made his London Sinfonietta debut at the age of 21, at the 1976 Proms.

Atherton had bowed out as music director in 1973 (though was to return later for a second stint); Snowman had gone the year before, whisked off by Pierre Boulez to manage IRCAM, and succeeded by Michael Vyner. Vyner, while conveying the image of an exuberant party host, proved a canny administrator and talent scout, and steered the London Sinfonietta from the sunshine of the mid-1970s through most of the long winter of the Thatcher years. He had his blind spots (there was no Gérard Grisey until 1995), but under him the London Sinfonietta began commissioning international composers of the front rank – Iannis Xenakis, Salvatore Sciarrino, Witold Lutosławski, Hans Werner Henze, Hans Abrahamsen, Elliott Carter – besides extending its reach to new British names from across a vast range of viewpoints: from Robin Holloway to Steve Martland, Michael Finnissy to Jonathan Lloyd, Brian Ferneyhough to Mark-Anthony Turnage, Colin Matthews to Nigel Osborne.

In October 1976 Vyner took the ensemble on an intercontinental tour that began on the west coast of Australia and ended on the east coast of Canada. There were wide-ranging festivals, curated by Atherton, of Schubert and Webern in 1978–79, Stravinsky in his centenary year of 1982, and Ravel and Varèse in 1983–84. There were ventures into opera, with Glyndebourne and Opera Factory. There were the beginnings of what was soon a strong education programme, encouraging school-age children to think like London Sinfonietta composers and work alongside the ensemble’s musicians. It was also during the Vyner years that Oliver Knussen and George Benjamin became indispensable members of the London Sinfonietta family, as composers and as conductors. Knussen’s Coursing of 1979 has totted up more than 60 London Sinfonietta performances, a total rivalled in the ensemble’s records only by the First Chamber Symphony of Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky’s Soldier’s Tale. Other much played pieces also date from this period: Birtwistle’s Silbury Air, Peter Maxwell Davies’s A Mirror of Whitening Light, Toru Takemitsu’s Rain Coming, George Benjamin’s At First Light, all London Sinfonietta commissions.

The London Sinfonietta offered a model to ensembles developing elsewhere, while any danger of uniformity was dispersed by the utterly different sounds of its commissioned works

Vyner’s strategies for keeping the London Sinfonietta on track in tougher times included beefing up the foreign engagements (there were tours of South America in 1981 and Japan four years later, as well as frequent European trips). Also, partly to ease touring but also for domestic economy, the basic personnel was tightened to 14 or so key players, soloists on woodwind, brass, keyboards, percussion and strings – the formation, roughly, of Ligeti’s Chamber Concerto, which the London Sinfonietta had introduced to the UK in 1971. Here, too, the London Sinfonietta offered a model to ensembles developing elsewhere, while any danger of uniformity was dispersed by the utterly different sounds of its commissioned works such as Hans Werner Henze’s Le Miracle de la Rose, Iannis Xenakis’s Phlegra and Hans Abrahamsen’s Märchenbilder. Vyner’s death, in 1989, was marked by a concert the next year that brought tributes from Hans Werner Henze, Harrison Birtwistle, Luciano Berio, Oliver Knussen and others, with conductors including Bernard Haitink and Esa-Pekka Salonen.

Paul Crossley – Vyner’s partner, and a long-time partner of the London Sinfonietta too, as solo pianist in works by Alban Berg and Oliver Messiaen – took over as artistic director, through the ensemble’s 25th anniversary. This was celebrated with a gala at the Barbican Hall, where many concerts were to take place through the mid-1990s. Markus Stenz as music director (1994–98) and Paul Meecham as general manager (1991–97) intensified the ensemble’s focus on contemporary work, and were succeeded in that by Oliver Knussen as music director. Gillian Moore, who had been education officer for a decade, took over as artistic director in 1998.

Meanwhile, the London Sinfonietta was welcoming new composers. John Adams first worked with the group in 1989 and answered a London Sinfonietta commission with his clarinet concerto Gnarly Buttons in 1996. Thomas Adès and Julian Anderson arrived on the same night in 1994, the former with Living Toys, one more in the list of London Sinfonietta hits. Later in the decade came others who, like Adès, had not been born when the ensemble started up, composers such as Richard Causton, Tansy Davies, Dai Fujikura, Sam Hayden and Morgan Hayes.

Of an earlier generation, two Finns – the post-impressionist Kaija Saariaho and energy-man Magnus Lindberg – became London Sinfonietta regulars, as did the hitherto little-represented Steve Reich and Wolfgang Rihm. Reich’s City Life, made of New York noises and instrumental tones, was co-commissioned by the London Sinfonietta. Others to be welcomed in from the cold, if sometimes only briefly, were Frank Denyer, master of stray sounds, and a varied bunch of senior European figures, from Niccolò Castiglioni to Morton Feldman, Sofia Gubaidulina to Arvo Pärt. Gérard Grisey’s Quatre Chants pour franchir le seuil – yet another London Sinfonietta commission, introduced under George Benjamin’s direction in 1999 with Valdine Anderson as soloist – brought the ensemble on stage for one of the last great works of the 20th century.

John Constable was there at the piano from the beginning, and Joan Atherton from the ensemble’s third year, playing second violin for almost a quartercentury alongside Nona Liddell.

On into the next, the London Sinfonietta continued to expand its range, under the leadership of Gillian Moore and, from 2007 onwards, Andrew Burke. After stepping down as music director, Oliver Knussen went back to being a frequent guest, along with George Benjamin. Other composer-conductors joined the London Sinfonietta roll, including Péter Eötvös and Ryan Wigglesworth, as well as new-music experts such as Martyn Brabbins, Ilan Volkov, Susanna Mälkki, Baldur Bronniman, Brad Lubman, Frank Ollu, Sian Edwards, Pierre-André Valade and André de Ridder.

With such varied talents available, the ensemble at last came to the brilliance-in-extremity of Helmut Lachenmann, the mechanical madness of Gerald Barry, the virtuoso soundpoetry of Unsuk Chin, the sophisticated eclecticism of Heiner Goebbels, the scintillant mists of Georg Friedrich Haas, the intensely felt fragmentation of Beat Furrer, and the unabashed oddity of Olga Neuwirth. Much younger composers, Luke Bedford, Francisco Coll, Samantha Fernando, Edmund Finnis, Ben Foskett, Larry Goves, Emily Hall, Mica Levi, Anna Meredith and Philip Venables are among those who have added notably to the London Sinfonietta’s repertory since 2001, several of these more than once – and to list them merely by name is quite unfair considering the variety of attitudes, resources and reference points they bring to the mix.

This history has also been a little misleading in drawing attention to change and rather underplaying continuity. For a new-music group, the London Sinfonietta has won remarkable loyalty from its players. John Constable was there at the piano from the beginning, and Joan Atherton from the ensemble’s third year, playing second violin for almost a quartercentury alongside Nona Liddell. Five other current players have served as principals since the 1980s.

Image: John Constable in rehearsal for Mica Levi's Under the Skin at Royal Festival Hall in 2017 © Domizia Salusest

Strong consistency in programming, too, has been a thread through the London Sinfonietta’s variegated halfcentury. The ensemble began with a dual perspective, looking not only to the present and immediate past but also to the more distant history of music where, as in so many more recent scores, wind instruments come forward. The former challenge rapidly took precedence, partly thanks to the London Sinfonietta’s immediate success in encouraging composers to write for it, and to the stimulus its concerts, broadcasts and recordings have given to successive generations of student composers.

Last year the London Sinfonietta played music by Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Hans Werner Henze and Karlheinz Stockhausen, as it did in 1968, and Luciano Berio, Harrison Birtwistle, György Ligeti and Iannis Xenakis, as it had by 1971, and Tristan Murail, Arvo Pärt, Steve Reich and Kaija Saariaho, as it had by the end of the 1980s, and composers just starting out, with whom it will go on into further decades, of music beyond today’s imagining.

Image: London Sinfonietta players at Southbank Centre's Royal Festival Hall, 24th January 2018

Published: 8 May 2018