GRISEY: QUATRE CHANTS

GRISEY: QUATRE CHANTS

A hauntingly disorienting masterpiece on death

Southbank Centre's Queen Elizabeth Hall, London

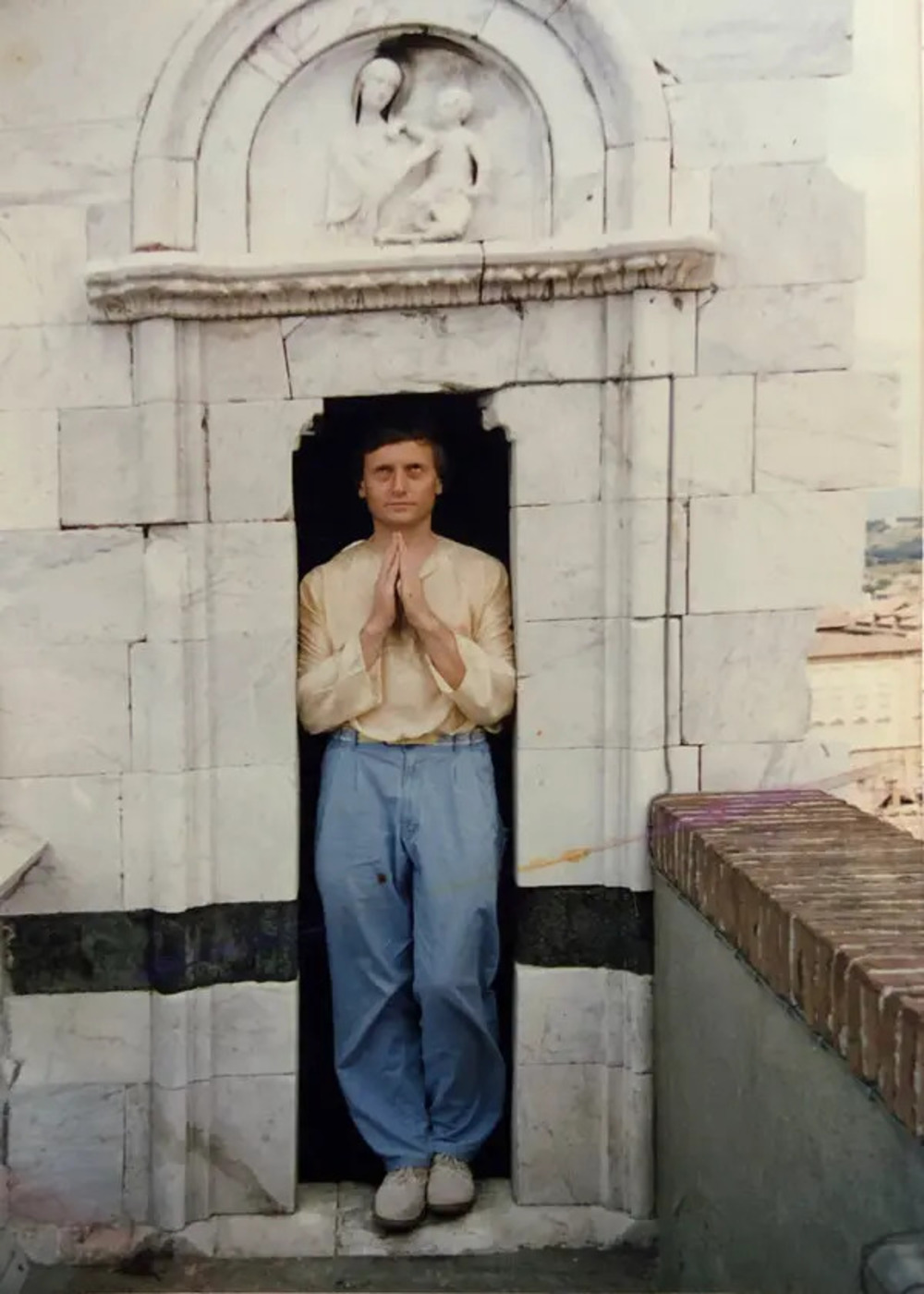

In a sense, Gérard Grisey (1946-98) is easy to situate in the French musical scene. He studied composition with Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatoire, briefly with Henri Dutilleux at the École Normale, and won a scholarship to study in Rome for two years (1972-4). But Grisey’s musical background was atypical: his instrument was the accordion, which he studied at the Trossingen Conservatory in Germany, and his origins were modest, with no artistic or intellectual connections. And his master-pupil relationship with Messiaen was, unusually, not close.

In Rome, Grisey got to know Tristan Murail, who initiated the ensemble and composer collective l’Itinéraire: Grisey’s music was often included in their concerts, but he was never an enthusiastic group-joiner and was not formally a member. Another important encounter in Rome was with the poet Christian Guez Ricord. Grisey later met composers including the Canadian Claude Vivier in the major contemporary music centre of Darmstadt, where he studied with Xenakis and Ligeti.

Today, Grisey is most associated with the term ‘spectral music.’ Spectral music is about the colour of sound: a note played by an instrument produces not only the actual pitch but also overtones – higher pitches that give the sound its individual instrumental timbre and quality. The overtones closest to the note can be heard most easily; those higher up the spectrum are less easily perceived, but they add colour. Low notes, especially when played by highly resonant instruments such as the piano, have particularly spectacular spectra. Typically, spectral music is harmonically slow-moving but constantly shifting in colour, as if gradually changing from the inside. To use an analogy suggested by Kaija Saariaho, another composer associated with spectralism, sound is placed under a microscope.

One characteristic Grisey spectral piece is Partiels (1975), which according to the composer’s biographer Jeffrey Arlo Brown is modelled on ‘the stages of human breath, with areas of inhalation, exhalation and repose.’ Even more tellingly, Brown noted that ‘physical desire, the breath, the beating heart’ were central to Grisey’s music. Listener perception mattered a great deal to Grisey, who had no interest in abstract compositional designs that are not apparent to the listener.

Spectral music is linked to contemporary trends: Liam Cagney mentions the impact of 1960s counterculture, noting connections to meditative music, Stockhausen’s Stimmung (which Grisey heard at Darmstadt) and concepts loosely derived from Buddhism or Hinduism. As a young man, Grisey was deeply religious, and while he moved away from his Catholic upbringing, he retained a broad interest in spirituality. Ancient Egyptian artefacts and spirituality were a particular passion, deepened by a visit to Egypt in 1974. We hear this impact in pieces including Anubis-Nout (1983) and Jour, contre-jour (1978), as well as the Egyptian funerary inscriptions used as the text of the second movement of Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil.

Grisey described Quatre chants as ‘a musical meditation on death in four sections – the death of the angel, of civilisation, of the voice, and of humanity. (...) The chosen texts belong to four civilisations (Christian, Egyptian, Greek and Mesopotamian) and have in common a fragmentary discourse on the ineluctability of death.’ Scored for soprano and 15 instruments, the ensemble is dominated by low-pitched instruments and brushing percussion sonorities. The work started as a tribute to Grisey’s mother, though other deaths that deeply affected the composer are memorialised, including Vivier’s and Guez Ricord’s. Its title is drawn from Vivier's unfinished Glaubst du, an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele? (1983) (Do you believe in the immortality of the soul?). The text of Vivier’s piece refers to being stabbed and crossing over into the unknown; while composing it, Vivier was, horrifyingly, murdered in his flat by a man he had met in a bar. Bob Gilmore wrote in his biography of Vivier that he composed ‘in large part in order to access an inner world: as a means of confronting pain, darkness, terror; as a means of negotiating a relationship with God; as a means of voicing his insatiable longing for acceptance and for love.’ While Grisey’s pains, darknesses and terrors were not the same as Vivier’s, his music has a similar impulse, both spiritual and deeply human.

Grisey’s Quatre chants are preceded by a breathy, brushing prelude at the limit of audibility, and separated by interludes (or in one case, a ‘false interlude’). The text of the first movement is Guez Ricord’s ‘La mort de l’ange’: while his poem uses simple words, its syntax is strangely ambiguous, as if connections are missing. Here, the soprano both sings and cries like a wild animal, her high voice contrasting strongly with the instruments descending towards the depths. The Egyptian movement, ‘The death of civilisation’, starts with an intoned text; it is desperately fragile, as if frozen in time.

The ‘death of the voice’, after the ancient Greek poet Erinna, features a solo violin (Barbara Hannigan compares it to a ‘strange bird’) and voice confronting groaning low-pitched sounds, as if breathing into a void. As the voice dissolves into the shadows, eerie percussive scuttling is picked up in the false interlude. In the fragmentary, enigmatic ‘L’épopée de Gilgamesh’, a Mesopotamian text with multiple Biblical echoes, sudden soprano and percussive outbursts shock but go nowhere. As the energy dissipates, the music descends and indeed almost vanishes, with performers calling to each other across a chasm. The work ends with a ‘Berceuse’, a rocking postlude which, according to Grisey, is ‘intended as a song of awakening for humanity.’ But this ‘song of awakening’ suddenly stops: we pass the threshold from sound to silence.

Grisey’s description of Quatre chants mentioned the ineluctability of death. It comes to us all, but Grisey had no idea on completing the work that his own death was so very close. Aged only 52, he had an aneurysm, fell into a coma and never regained consciousness. While Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil was in no sense conceived as his autorequiem, it is irresistible for us to consider it as such.

Caroline Potter

Published: 25 Nov 2025