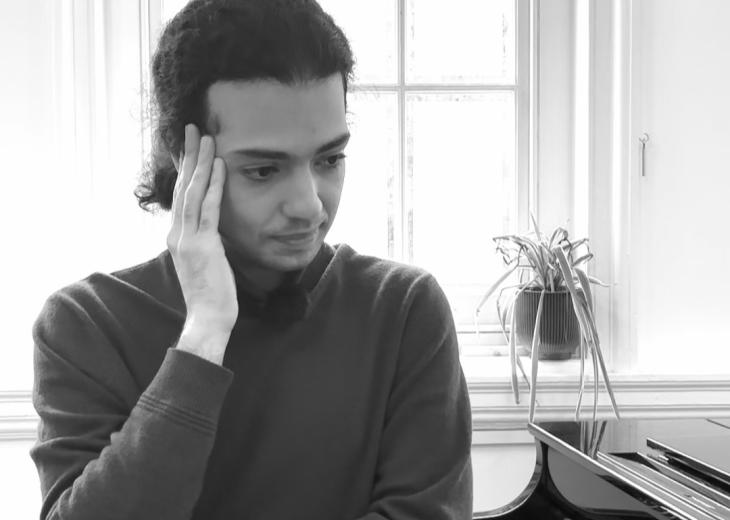

To mark the world premiere of his new work as part of Writing the Future 5, we sat down with composer Ashkan Layegh ahead of its first performance at London Sinfonietta & Marius Neset.

Developed for string quartet, the Phemo Quartet, and a ‘screen quartet’ of visual and text-based elements, the piece explores ideas of ephemerality, physicality and recurrence - inviting listeners into a sound world where material appears, dissolves, and returns in unexpected forms.

In this interview, Ashkan reflects on the influence of his Persian musical heritage, the role of viscerality and embodied performance in his work, and how cycles of repetition and transformation shape the music’s inner logic - offering audiences multiple ways to listen, interpret, and experience the piece.

Can you share a little bit about your piece?

The piece is a multimedia one for two quartets: a string quartet and a quartet of mine, the Phemo quartet, which includes electric bass, alto saxophone, piano and drums. There is also what I would refer to as a screen quartet, which has certain elements of visuals, illustrations, texts about the process of the piece and the anecdotes about the piece itself. These three things happen at the same time, so the piece is exploration of three different pieces in one piece. Each of them could individually work on its own, but they all came together to this final multimedia product.

It’s not about just watching what is going on on the screen or just watching one quartet or the other. It’s about the general experience we get from all three things happening at the same time.

What was the initial spark for the piece, and how did the concept of ‘ephemerality’ guide your process?

I think none of us can really deny the material truths of every single one of us: the fact that life eventually ends at a certain point, and the experience of owing a human body, and how this affects us. This is one thing we can all be certain exists. I’ve always been quite interested in exploring ideas of viscerality in my music, and see how much the physical material can make some sort of intimate relationship between the performers, my music, and also my audience. This has been always present in my work.

At the same time, I’ve been trying to acknowledge that this physicality eventually ends. My work can be put into certain blocks of time where we have very intense, consistent physical activities that’s happening, and then suddenly we cut and go to something else, and then we cut and get something else. But they recur. There is some sort of causality, as something moves from one thing to another to another, but also comes back in different juxtapositions. In that way the material is quite ephemeral: what you’re hearing now, you will definitely not hear 40 seconds later, but it will definitely recur.

How do cycles and self-reflexivity shape the piece?

A big part of why music is very much about cataloguing, how the systems of power try to catalogue our day-to-day life and to try to categorize it in ways that eventually fail - whether it's gender, sexuality, race. This is something I'm deeply passionate about exploring, because today is this notion, tomorrow is another, and it always fails to encompass our collective existence.

I often like to explore these notions in my work as much as I can - not in a very explicit way, as in my text, but in the way the music works and sounds. The music gives you different possibilities, but it never gives you the ultimate possibility. The music is constantly trying to deny itself, deny the way it's getting organized, and reorganize itself through these endless cycles. By the end, I think my audience would be quite perplexed to find that there's no definite truth within the piece. I'm just trying to give them different possibilities for them to create whatever narrative they would like to create out of it.

Your music draws from Persian influences but reimagines them in fresh ways. What does ‘tradition’ mean to you in the context of modern composition? And how do Persian musical traditions or aesthetics influence your sound world?

As someone who grew up in Iran, my dad is quite a well-known Persian musician and composer, I think this has been in my DNA since I was a child. In terms of music, it’s very much a syntactical influence, it’s not something on the surface that I can pinpoint as ‘this is a Persian influence.’

My music deals a lot with the idea of cataloguing, and in Persian music, in terms of improvisation, one thing is the great variety of ornamentation that they have. The structure is actually quite solid. There’s a way that interpretation of the music happens within a very solid structure, where different ornamentations are explored in different ways. I think this notion of exploring something within a solid structure but then changing it and creating a certain level of interplay, is something that is quite present in my music.

The piece brings together three quartets (one instrumental, one jazz-based, and one visual). Can you talk about how these layers interact, and what audiences might expect to see as well as hear?

A string quartet is deeply rooted within the tradition of classical music and its performance practice as a chamber ensemble. My ensemble, of piano, electric bass, alto saxophone and drums, is also set up in the jazz tradition. Whether the music actually deals with jazz and classical music is another question, but certainly the instrumentation appears to be, and I was always quite interested to see how I can write a piece of music that is actually two different pieces in one.

The string quartet works completely independently on its own, and at the same time my quartet, the Phemo Quartet’s material, also works on its own. The piece is two distinct quartets, but they somehow come on top of each other and try to make some sort of dialogue with each other. The dialogue is not one that you might expect – this is doing this, and the other one is doing that, and let’s see how I can relate that. The dialogue is very much about the dissociation between the two quartets. It’s seeing how we can write a piece that dissociates certain elements and explores the different qualities of both at the same time.

In the same manner, the visual is doing the same thing. I consider the visuals completely independent of the music, but at the same time very related to it. Both the music and the visuals follow the same structural patterns. The visuals also have four different elements, so it's very much a quartet as well: visuals, illustrations, notes about the process of making the piece, and anecdotes about the piece. All these four work together in the same way that both quartets are dissociated, the visual material also gets dissociated.

There’s a strong crossover in this concert between jazz and classical composition. How do you approach improvisation and structure in your writing? Where do you draw the line, or do you prefer to blur it?

Improvisation somehow expresses a real form of creation in front of the eyes of the audience, and I think this is very important because most music we hear is normally composed, and then we are exposed to it. This is a spirit that is present in many different types of music. I am deeply into free jazz and free improvisation, and I quite often like to inject that spirit into my music, convincing the listener that what they're hearing is a product of real improvisation, of real music-making in front of their eyes.

But since the music works in blocks and you don't know what's going to happen 40 seconds later, I suddenly cut. Then you find yourself in a completely new territory. You acknowledge that what we're hearing was actually not a product of real creation, but an artificial imposition of improvisation.

How does it feel to have your piece premiered alongside a world-renowned artist like Marius Neset?

Marius is one of the key figures in European jazz, and it's an absolute privilege for not just me, but also our ensemble, to share the stage with him on the same night. In terms of our music, Marius’ music is very much driven by European jazz and the European tradition of improvisation. In contrast, my music is very much coming from European composition tradition, but also my improvised background (apart from Persian music) is very much coming from American jazz. I think the audience will find it quite interesting to witness two different pieces that are trying to create a dialogue between two different traditions and two very different ways of thinking, and see how they can make certain connections between the traditions of their own.

Ephemerality and Recurrence premieres on Thursday 20 November at the Southbank Centre's Queen Elizabeth Hall alongside Marius Neset's Changes, as part of the EFG London Jazz Festival.

Published: 6 Nov 2025