SOUND ACROSS A CENTURY / 1

SOUND ACROSS A CENTURY / 1

Impressionism to Spectralism

Queen Elizabeth Hall, London

As part of our Sounds Across a Century series, exploring the musical evolution of the 20th century, Robert Adlington looks at the works of Schoenberg, Webern, Lutyens, Ligeti and Birtwistle, and how they reinvented and broke with established musical forms.

In truth, musical modernism is characterised by the coexistence of contrary tendencies: on the one hand, a sense of acute responsibility to the path of history; on the other, a preoccupation with rupture, the forging of the unprecedented. This dual anxiety towards past and future marks every element of the Sounds Across a Century 2 programme, beginning with Schoenberg’s earliest experiments with atonality in 1909, which entailed the abandonment of harmonic principles that had endured for centuries. Schoenberg’s theoretical writings presented atonality as the logical extension of the ambiguities of late nineteenth-century music. But he was equally in thrall to the shock of the new – especially Fauvist and Expressionist art, and Freud’s new theories of the human unconscious.

Schoenberg described his Five Pieces for Orchestra (1909) in terms that encapsulate the cycle’s expressionist leanings: ‘they are absolutely not symphonic – no architecture, no structure. Merely an uninterrupted interchange of colours, rhythms and moods’. Each movement, lasting from two to five minutes, presents a concentrated study in contrasting moods, ranging from the wildly nightmarish to the tensely subdued.

By the 1920s, Schoenberg had already moved on to a radically new composition method: serialism or twelve-tone composition, in which a single sequence of the twelve notes within an octave provides the basis for an entire work. For many of Schoenberg’s followers, serialism seemed (as Boulez later asserted) a ‘necessary’ development, providing a superior basis for the exploration of the atonal revolution. Yet it also reflected Europe’s sharp turn, after 1918, from the decadence and indulgence of the pre-war years, towards rationalism and order. Listening to Anton Webern’s Quartet Op. 22 (1930), one is struck more by the differences than the similarities with the early atonal work of his teacher, Schoenberg.

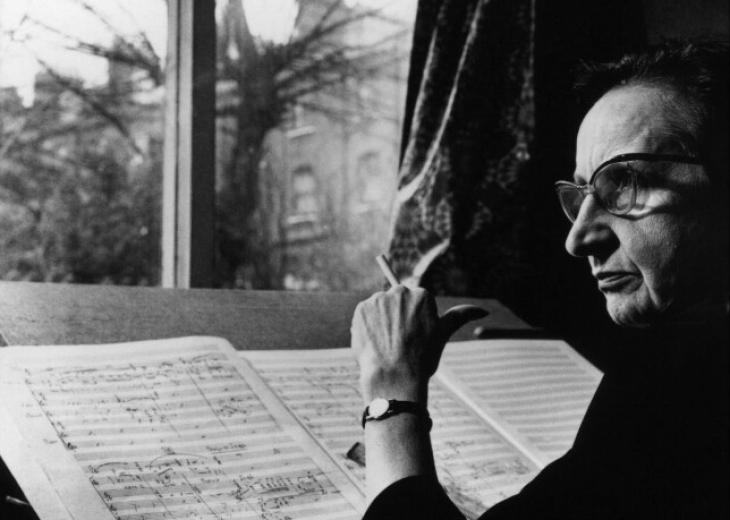

Webern found great inspiration in poetry and nature; but in his mature serial works, these worldly stimuli are distilled into a music of unearthly discipline, in which (as in Mondrian’s paintings) it is difficult to separate figurative remnants from abstract geometry. Amongst younger European composers of the 1950s, Webern’s reduction of composition to its structural fundamentals chimed with a felt need to rebuild musical culture from scratch after the cataclysm of the second world war. But the question of how to advance Webern’s legacy met with little general agreement. Elisabeth Lutyens, who pioneered serial composition in Britain, had no compunction about using it for illustrative and expressive purpose – as she did in numerous film and television scores.

Her Six Tempi op. 42 (1957) adheres to the soloistic style characteristic of Webern – the ensemble’s ten instruments never play all together – but Lutyens

carefully fashions the brief contributions of individual instruments into longer melodic lines and chordal textures, to great poetic effect. Lutyens originally intended each short movement to be named after a Baudelaire poem – Morning Twilight; Mists and Rains; Landscape; Fountain; Nocturne; Dusk – but these titles were later suppressed in favour of the brisk objectivity of the movements’ different metronome markings.

For the young Pierre Boulez, on the other hand, the ‘necessity of twelve-tone language’ precluded dalliance with the ‘anecdotal’ – which meant anything that smacked of the everyday and the referential. Boulez is a good example of how the unpredictable twists and turns of musical modernism could arise from shifts in outlook on the part of a single individual. A case in point is Boulez’s Dérive I (1985), whose title relates both to the derivation of a six-note series from the surname of his friend and patron Paul Sacher, and the dérive’s secondary connotation of ‘drift’. A set of interconnected six-note chords establishes a basic terrain that the small ensemble explores with improvisatory freedom. In the first half of the piece, slowly evolving sonorities are enlivened by trills and increasingly elaborate ornamentation; in the second, individual instruments strike out more independently, creating a kind of flexible melodic counterpoint that would have been unimaginable in Webern. Rather, it is the flute of Debussy’s Faun that is briefly audible towards the end. By the time of Dérive I, the modernist enthrallment to serialism had long since been superseded by other obsessions, other necessities. Not infrequently, these included the necessity to challenge earlier modernist tenets.

Throughout the 1960s, Ligeti focused on textures rather than individual notes, a ‘swerve’ in the history of composition that could nonetheless claim to be a historically necessary response to the new sonic domains being opened up by electronic technology. Ligeti’s Melodien (1971) represents a culminating point in his exploration of texture. From the start we hear the multiple layers of repetitive instrumental figuration characteristic of many of Ligeti’s earlier works. But as the piece proceeds, these layers are loosened so that individual strands can be discerned separately; what was texture starts to become melody. Ligeti’s title served as a polemical riposte to earlier modernists who had rejected the expressive associations of melodic writing. Indeed, the work positively revels in its rediscovery of musical elements that serial orthodoxy had discouraged: audible repetition, moments of tonal harmony, and, at the work’s very centre, the pure consonance of the octave.

At what stage, then, does modernism’s preoccupation with rupture lead to a rupture with modernism? Postmodernists propose the pleasures of the present as a balm to heal modernism’s anxiety towards past and future, but arguments rage as to whether this move represents an extension of a modernist urge, or precisely the compromise that modernism repudiated. In any case, an alternative genealogy of musical modernism had already queried the dichotomy of past and future: in the music of Igor Stravinsky, the new became a means to rediscover (or reinvent) the very old.

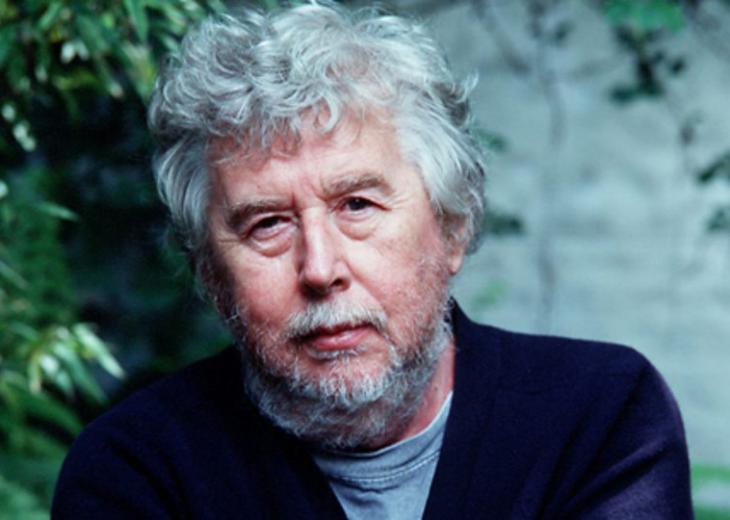

Sir Harrison Birtwistle’s music, following Stravinsky, draws upon the timeless fundamentals of pulse, song and repetition; but, approached through the experience of serialism and the twentieth-century rethinking of musical texture, the effect is to collapse ancient and modern, reminding us that no history can be known independently of the present. Birtwistle’s advocacy of unilinear history belies his music’s rupturing of modernist certainties.

The title of Birtwistle’s short Cantus Iambeus (2004) instantly evokes an imaginary past. But where is the song? For that matter, where are the iambic (short-long) rhythms? Rather than present an ‘iambic song’ unambiguously, Birtwistle’s thirteen instruments appear to be searching for it, presenting an instrumental theatre of cautious liaisons, disagreements, and nervy shifts of attention. More often than not, it is jerky accompanimental textures that hold the stage, as if the melody line is being hailed in absentia. Only at the end, with a reiterated E ricocheting around the ensemble, do we sense the common purpose necessary for song to emerge – at which moment, the music stops.

Published: 5 Mar 2020